Theories of Thinking: Excavating the Paideia Underlying Philosophic Defenses

Preamble

Athens entered the fourth century BC as a fallen city-state; the great Periclean empire had suffered a defeat in 404 BC after fighting for thirty years in the Peloponnesian war. Werner Jaeger, in his infamous writings on paideia, tells us that “the fourth century is the classical epoch in the history of paideia if we take that to mean the development of a conscious ideal of education and culture” (Jaeger 5). The period was a time of inward regeneration, and thus imaginations loomed large as to how to rebuild the state and reform the individual for a stronger and better Athens. The education of the previous century was centered on an aristocratic principle of privileged education, which made it possible for only those of divine ancestry to acquire arete. After the fall, philosophers took up the task of institutionalizing a system of education for the whole community, and not just a few noble families. Their eyes broadened in scope and in stature to take on the futuristic endeavor of determining how the city-state and the individuals therein can act in tandem without disruption. Along with proposals for the proper structure of the state came conclusions about the proper form of education; in fact, Plato’s Republic is a leading exemplar of how views of governance can be synchronous with experimental methods of teaching.

Concentrating on Plato and his student, Aristotle, I will demonstrate the dual nature of their philosophic works, and ultimately introduce my theory that each philosophic work was both a proposal for and an experiment in a new way of thinking, thereby carrying on the dynamic nature of paideia. Both philosophers practiced their proposed method of education while teaching it in their works. They simultaneously practiced and preached, taught and molded, proposed and instilled. In one sense, they were experimenters of their own theories of education, but in another, they were founders of novel proposed ways of learning.

Plato’s Republic: An Apology of Philosophic Education

Plato shepherds his readers along a katabatic (or perhaps, anabatic) journey of the notoriously abstruse elenchus until finally, Socrates’ conclusion on the meaning of ‘justice’ becomes clear: justice refers to a harmonious division of labor and equitable practice among the elemental parts of both the state and the individual soul. Despite the eventual clarity we reach at the end of the dialogue regarding the definition of ‘justice,' I was left mulling over how Plato guided his readers along an ascent to his conclusions.

My hypothesis is that the divided line Socrates presents in Book VI (509d-511e) provides us with the four stages of reasoning that students would follow to attain a philosophic education. The first stage consists of ‘εικασια,' which literally means the apprehension by means of appearances like images, shadows, or phantasms. The activity of this stage is imitation, which is necessary to establish hypotheses, literally fromυποτιθημι meaning ‘things set down’. The εικασια are distinct from ειδωλα, which are images Socrates does not endorse because of their corruptive value. He speaks of the ειδωλα when criticizing the influence of the poets and sophists on the minds of youth. The second stage of the realm of opinion (δοξα) is ‘πιστις’ meaning belief. Socrates does not define ‘πιστις’ in depth, but I gauge the essence of the term to mean the acceptionof uncertain convictions. The activity is sense-perception, since belief derives from the cognition of concrete particulars.

We move from δοξα to the realm of knowledge (επιστημη) for the last two stages; this transition is important because we no longer need images to form hypotheses, but rather proceedwithout images to found first principles (510c). The third stage is διανοια or ‘thought,' which consists of the ability to grasp general concepts. The activity of thought can be likened to the study of geometry, in which models and diagrams are made to make claims about the properties of dimensions in themselves. The fourth and final stage is νοεσις or ‘understanding,' which is the power to grasp the Forms. The exercise consists of participating in dialectic “…without making use of anything visible at all, but only of forms themselves, moving on forms to forms, and ending in forms” (511c). Socrates does not practice ‘understanding’ in the Republic, but works through the challenge of guiding his interlocutors through the first three stages. He “…abandons the quest for what the good itself is…” for the sake of the magnitude of the task and, instead, appeals to certain kinds of useful imagery to convey his philosophical ideas; in the process, he demonstrates the power of visualization in education and the ability to re-construct a society’s distinctive culture, paideia, by redirecting its point of view (506e).

INTELLECT (nous) Understanding (noesis)

Thought (dianoia)

VISUAL PERCEPTION Belief (pistis)

(to horaton) Imagination (eikasia)

Figure 1: The Dividing Line

Stage 1: Distinguishing Between Useful and Destructive Image-Making Art

In Books I and II of the Republic, Socrates’ interlocutors cite Greek poets in their responses to Socrates’ imploring questions -- Cephalus refers to the lyric poet Pindar when defining the benefits of wealth (331a), Polemarchus cites Simonides when giving a definition of the craft of justice (331d), Adeimantus quotes Archilochus when describing the attitudes towards virtue and vice (365c). Book X comes full circle to again take up the question of the educative value of poetry. Socrates says “…an imitative poet puts a bad constitution in the soul of each individual by making images that are far removed from the truth and by gratifying the irrational part, which cannot distinguish the large and the small but believes that the same things are large at one time and small at another” (605b). This reference to distinguishing between ‘large’ and ‘small’ is a reminder of Socrates’ method of investigation at the start of the Republic: “…we should adopt the method of investigation that we’d use if, lacking keen eyesight, we were told to read small letters from a distance and then noticed that the same letters existed elsewhere in a larger size and on a larger surface” (368d). We discover that the large letters denote the position of justice in a city and the small letters denote the position of justice in an individual. Socrates criticizes the poets for their erratic dissemination of images without recourse to the disruption of order in the soul of an individual. Adeimantus relates to Socrates that the poets’ stories teach that the rich can “…persuade the gods to serve them” by means of expensive rituals and pleasant games, but the poor priests and prophets do not have the means to free themselves from punishment by means of appeasing the gods (364c); therefore, it is profitable to be unjust, because “…we get the profits of our crimes and transgressions and afterwards persuade the gods by prayer and escape without punishment” (366a).

Recognizing the impressionable effect that poetry can have on the “…souls of young people…(and) impression of what sort of a person he should be and of how best to travel the road of life”, Adeimantus asks Socrates to take on the task of demonstrating how the effects of ‘justice’ benefit the soul of a person (365b, 367d). Adeimantus already grants that the effects of justice may remain hidden from gods and human beings, but he leaves it up to Socrates to διερευνησασθαι (to track down, search through, examine closely) the nature of justice and injustice and the αληθης (unconcealed, truth) of the benefits of each (367e). Socrates maintains the theme of investigation and discovery throughout the dialogue in an effort to include his interlocutors on his search, but, as I will demonstrate, he is dually experimenting with a new method of teaching. As the old saying goes, the best way to hide something is to put it in plain sight. The aim of his paideia is conversion of the soul (literally, from converto meaning to turn or rotate), which is dependent on graduating his listeners towards seeing the poetic images as mere shadows and his constructed visuals as pragmatically valuable for the good of the soul and the polis. His method of teaching is processual, not automatic. In Book VII, he says, "Education isn't what some people declare it to be, namely, putting knowledge into souls that lack it, like putting sight into blind eyes…Education takes for granted that sight is there but that it isn't turned the right way or looking where it ought to look, and it tries to redirect it appropriately" (518d). Socratic paideia is a “turning around” of the whole soul – as I will demonstrate, he educates by using the power of dialectic to translate words into verbal pictures. By feeding the imagination with a different set of images that serve the purpose of distinguishing the advantage of the good over the bad, he can then begin the ascent towards educating solely about the good.

The distinction begins in the Greek vocabulary he uses to describe the ‘images’ conjured up by the poets versus the ‘images’ he endorses. He describes the ‘images’ or ‘shadows’ produced by the old paideia of poetry as ειδωλα (365c, 382b, 443c, 515c-516b, 520d, 532c, 583b, 599b, 601a-c). Ειδωλον is defined by LSJ as an image, a phantom, any unsubstantial form, image reflected in a mirror or water, idol, or likeness. In contrast, Socrates refers to the images he endorses as εικονες(401b, 510b, 515c, 517b-d, 531b, 588c). Εικων is defined by LSJ as an image, portrait, simile, comparison, pattern, or archetype. I will present you with a series of examples of εικονες.

The Republic begins with an ecphrastic image of two cities – the city of pigs, or what Socrates refers to as the “true city…the healthy one”, which functions as a self-sufficient economic organization, and the “…luxurious city…a city with a fever” (372e). Socrates was satisfied with the sketching of the first, unadorned city, because it was in essence a model for the harmony of specialization – the proper functioning of the city is a harmony of parts, with each part working to its own appropriate function. Socrates describes the creation of the second city as such: “We must increase it in size and fill it with a multitude of things that go beyond what is necessary for a city—hunters, for example, and artists or imitators, many of whom work with shapes and colors, many with music. And there’ll be poets and their assistants, actors, choral dancers, contractors, and makers of all kinds of devices…” (373c). The second city, which represents a more realistic image of fourth century Athens, is filled with people who fill the environment with superfluous, unnecessary ειδωλα. The healthy image of order and unity in the original city stands in stark comparison, as a εικων, to the fevered image of the second city, with its myriad of actors and arts, in a state of disorder and disunity.

As with the image of the original city, Socrates begins with an image of the philosopher-king, then demonstrates how changes to the ordered image beget inferior ‘εικονες’ of four forms – the timocratic man, the oligarchic man, the democratic man, and tyrannical man. The purpose of the task is “…to sketch (fr. υπογραψω) the shape of the constitution in theory, not giving an exact account of it, since even from a sketch we'll be able to discern the most just and the most unjust person" (548d). Socrates shows the benefits of justice and the harms of injustice by comparing images (εικονες) of the καλλιπολις and the soul of a citizen of the city to its successive rivals. His argument rests on the principle that one must look at the whole of a city and soul to discern the superiority of justice. In each of the four unjust cities, the ruling class may arguably be happy, but only in the just city does the philosopher-king rule in the best interest of all the classes. The account of the life of a philosopher-king is not self-sacrificial. Rather, by giving back to society, the philosopher serves his own interests. The just city has provided a bird’s nest for nurturing the cultivation of παιδεια that allows for the philosopher to work towards realizing his nature and full potential – as Socrates says, “You’re better and more completely educated than the others and are better able to share in both types of life [i.e. the practical life of ruling the city and the theoretical life of studying the good itself]” (520b). With reason as the ruler of the philosopher-king’s soul, he will be able to look beyond immediate advantages and make advantageous decisions that benefit all parts of the city and all parts of the soul. The image (εικων) of law and order in the soul of the philosopher-king stands in contrast to the soul of a tyrannical man. Like an addict, the tyrannical man is dominated by insatiable appetites, so that he can neither fulfill his own self-interest nor have concern for the needs of others. The εικονες of the types of constitution and types of soul serve a comparative purpose for visualizing the grades of dissolution that follow from the image of harmony in the καλλιπολις and in the soul of its ruler.

He speaks of “…fashioning an image of the soul in words” (588c). Since “…words are more malleable than wax and the like”, he acts as a metaphysical artist to mold and sculpt (in Greek, ‘πλαττειν’) creatures to represent the invisible parts of the tripartite soul. Desire, spirit, and reason are psychological concepts that Socrates makes more tangible by likening a many-headed, multicolored beast to represent desire, a lion to represent spirit, and a human being to represent reason. The image of a single human being is merely an outer covering for the three creatures dwelling in its soul. Socrates intends to make use of his excavation of the inner workings of man’s soul as a visual tool. Those who say injustice profits see only the outer human being. In fact, the inner soul of an unjust man is controlled by the multiform beast who wreaks havoc on the peace of the soul; whereas the inner soul of a just man is controlled by an inner human being who feeds the beast and domesticates the lion. He molds an image that likens a political ruler of parts of a city to a psychological ruler of parts of a soul. Just as it is necessary to establish law and order in a city by means of a constitution, it seems visibly necessary to also set down an anima constitution in children’s souls by equipping them with the best internal ruler (591a).

Poet Imitators vs. Metaphysical Artists

Within each aforementioned example of a εικων I have elaborated on, as well as in the others I have cited, Socrates has used particular verbs to describe his production of verbal images: πλαττω (meaning “to mold” or “to sculpt”), (υπο)γραφω (meaning “to write” or “to sketch” or “to paint” or “to propose (a law)”), εικαζω (meaning “to liken” or “to compare” or “to approximate”). He intends to distinguish himself from the actions of the poets, who μιμεισθαι, or ‘imitate’. In fact, he bans imitative poetry from the καλλιπολις in Book 10, saying, “…poetry should be altogether excluded…Between ourselves—for you won’t denounce me to the tragic poets or any other of the imitative ones—all such poetry is likely to distort the thought of anyone who hears it, unless he has the knowledge of what it is really like, as a drug to counteract it” (595b). The antidote to μιμεσις is "knowledge of what it is really like," emphasizing the gap Socrates has spotlighted between the realm of appearances and “what truly is”. He describes the work of an imitator as such:

“We’re agreed about imitators, then. Now tell me this about a painter. Do you think he tries in each case to imitate the thing itself in nature or the works of a craftsmen?

The works of a craftsmen.

As they are or as they appear? You must be clear about that.

How do you mean?

Like this. If you look at a bed from the side or the front or from anywhere else is it a different bed, without being at all different? And is that also the case with other things?

That’s the way it is—it appears different without being so.

Then consider this very point: What does painting do in each case? Does it imitate that which is as it is, or does it imitate that which appears as it appears? Is it an imitation of appearances or of truth (φαντασματος η αληθειας)?

Of appearances (φαντασματος)

Then, imitation (μιμεσις) is far from the truth, for it touches only a small part of each thing and a part that is itself only an image (ειδωλον). And that, it seems, is why it can produce everything. For example, we say that a painter can paint a cobbler, a carpenter, or any other craftsman, even though he knows nothing about these crafts. Nevertheless, if he is a good painter and displays his painting of a carpenter at a distance, he can deceive children and foolish people into thinking that it is truly a carpenter.” (598a-c)

The mimetic artists are akin to the shackled prisoners who are able to only see the shadows and reflections of objects on the walls of the Cave. Having been raised in a world of shadows, the imitators are blinded by the light and portray the world of shadows incorrectly as reality. They are stuck in a realm of conjecture, as their images (ειδωλα) fail to relate perceptible objects of the physical world to imperceptible truths.

Both the poet and the philosopher-king have been described as “painters” (or ζωγραφος), but their objects of art are clearly wholly different. The poet, as a painter, imitates and draws (γραφη) mere appearances of external objects he sees in reality. However, the philosopher-king, as a constitution-painter, "…as they work, they'd look often in each direction, towards the natures of justice, beauty, moderation, and the like, on the one hand, and towards those they're trying to put in human beings on the other. And, in this way, they'd mix and blend the various ways of life in the city until they produced a human image based on what Homer too called "the divine form and image" when it occurred among human beings" (501b). The philosopher-kings are equivalent to metaphysical artists, who “paint” the kinds of images that can be used by viewers to help them work toward access to the imperceptible concepts of what really is. For Socrates, the cognitive “paintings” do not function merely as art or pleasure, but as educative works that can have a powerful influence on shaping the contours of human imaginations. The images produced by the art of mimesis, or imitation, do not align with reality: for example, the image of two cars approaching the same intersection, from your vantage point, may seem to indicate an inevitable crash. However, the appearance of the two cars from another angle might show another road to the right, and, with this detour, the cars would drive in different directions instead of heading straight into a collision.

Figure 2: Appearance vs. Reality

Stage 2: Conditioning Souls to Believe for the Sake of “Usefulness”

Beliefs can have consequences. Socrates may have relegated the power of images to stretching and, sometimes distorting, the imagination of the human mind, but he regarded the institution of belief (πιστις) as having the power to govern people’s action. He applies a test to Homer’s work to investigate whether his poetry has helped guide the governance of his listeners:

“But about the most important and most beautiful things of which Homer undertakes to speak—warfare, generalship, city government, and people’s education (παιδεια)—about these it is fair to question him, asking him this: “Homer, if you’re not third from the truth about virtue, the sort of craftsman of images (ειδωλου δεμιοργου) that we defined an imitator (μιμητην) to be, but if you’re even second and capable of knowing what ways of life make people better in private or in public, then tell us of which cities are better governed because of you, as Sparta is because of Lycurgus, and as many others—big and small—are because of many other men? What city gives you credit for being a good lawgiver, who benefited it, as Italy and Sicily do to Charondas, and as we do to Solon? Who gives such credit to you? Will he be able to name one?”

“I suppose note, for not even the Homeridae make that claim for him.”

…

“But Glaucon, if Homer really had been able to educate (παιδευειν) people and make them better, if he’d known about these things and not merely about how to imitate them, wouldn’t he have had many companions and been loved and honored by them? … “Instead, wouldn’t they have clung tighter to them [Homer and Hesiod] than to gold and compelled them to live with them in their homes, or if they failed to persuade them to do so, wouldn’t they have followed them wherever they went until they had received sufficient education (παιδεια)?” (600a-e).

Socrates argues that Homer’s works had not taught people or cities how to be better, and thus Homer was merely an imitator, not an educator. Socrates hones in on the power of belief to inspire action in the direction of the good when constructing the καλλιπολις. He assigns the philosopher-kings of the city, also referred to as the "constitution-painters," with the task of producing “useful falsehoods”. The “usefulness” of these constructed fictions is that, if believable, they can prompt a whole citizenry to act as if they were able to understand the truth of justice. The citizenry of a just city is ordered into a hierarchy of classes, harmonized like a brotherhood, and stabilized socially. The benefit of the story of the myth of the metals (415a-c) is that it helps bring about the order of a just city without the impossibility of teaching and practicing dialectic with the whole citizenry. Since storytelling can be so powerful, Socrates assigns the responsibility of producing yarns to the philosophers only, who can make use of beliefs by tying them to illuminated metaphysical truths.

Stage 3: Constructing Models of a ‘Socratic Geometry’ of Philosophy

The third stage in Socrates’ ladder of παιδεια consists of model-making. Socrates recognizes the use of modeling in mathematics and applies it to language. When developing the education of the Guardians, Socrates discusses the necessary and appropriate subjects with his interlocutors. He speaks of geometry as a subject in the realm of “thought” (διανοια), because “Geometry is knowledge of what always is. Then itdraws the soul towards the truth and produces philosophic thought by directing upwards what we now wrongly direct downwards” (527b). In order to understand why he thinks that the process of solving problems in geometry produces philosophic thought, we must return to the discussion of the divided line at the end of Book VI. Socrates says, “…although they [geometers] use visible figures and make claims about them, their thought isn’t directed to them but to those other things that they are like. They make their claims for the sake of the square itself and the diagonal itself, not the diagonal they draw, and similarly with the others. These figures they theymake and draw, of which shadows (σκιαι) and reflections in water are images (εικονες), they now in turn use as images (εικονες), in seeking to see those others themselves that one cannot see except by means of thought” (510e). Geometry is not about perceptible objects, since perceptible things are only an approximation of a geometrical truth. If I draw a rectangle, the figure is only approximately flat, the lines are only approximately straight, and its vertices are only approximately at a 90-degree angle. Thus, geometers cannot and do not use calculation and measurement to arrive at truths about geometrical shapes. Instead, they use objects of the physical world to visualize the ideal figures under certain assumptions and identify theorems that approximate the truth of perceptible objects.

For example, a geometer could study the motion of rowing blades to help visualize various angles. During rowing practice, we would look at videos in slow-motion to analyze the motion of the oar and discuss how to improve the strength of its impact with the water. Our goal was to move the blades into the water at the right angle at the right moment (what the Greeks would call “καιρος”) at the catch, so that the maximum amount of energy stored in the shaft at the beginning of the drive would be applied to the water and accelerate the boat forward. The perfect rowing stroke would likely consist of a series of optimally timed blade angles from 180 degrees to 90 degrees, so that the oar has two effects: a “backsplash” at the catch and a “bending of the oar shaft” through the drive. The “angle” itself as it exists between the blade and the water would not be perfect, because the line of the blade is not perfectly straight and the surface of the water is not perfectly flat. However, this visual image would be a helpful aid for a geometer to arrive at a definition that approximates an “angle” in the physical world: “the space between two intersecting surfaces at or close to the point where they meet.

Socrates considers the visual images and the geometric models of the true things as they exist as preludes, tools for warming up, to “the song that dialectic sings” (532a). He says “It (dialectic) is intelligible, but it is imitated by the power of sight. We said that sight tries, at last, to look at the animals themselves, the stars themselves, and, in the end, at the sun itself. In the same way, whenever someone tries through argument and apart from all sense perceptions to find the being itself of each thing and doesn’t give up until he grasps the good itself with understanding itself, he reaches the end of the intelligible, just as the other reached the end of the visible” (532a-b). The intermediate step towards understanding, which consists of a dialectic discussion in only invisible Forms, is to construct models that visualize the essence of perceptible things. As we demonstrated in the example above, looking at a blade and modeling it geometrically as two surfaces that meet at a single intersecting point helps define the essence of an “angle” as a concept. A model has cast off all incorrect hypotheses and landed on a theorem that is universally applicable and the closest approximation to the perfect figure of a perceptible thing.

Socrates makes use of models strategically throughout his dialogue. In fact, he has been “…making (fr. ποιεω – dual meaning of “to compose poetry”) a theoretical model of a good city” throughout the entire dialogue, but it was not highlighted until Book V that “…it was in order to have a model (παραδειγμα) that we were trying to discover what justice itself is like and what the completely just man would be like, if he came into being, and what kind of man he’d be if he did, and likewise with regard to injustice and the most unjust man…” (472d). Not only is a model necessary to best approximate a fine and good city, according to Socrates, but it is essential that young people maintain “…no models (παραδειγματα) in themselves of the evil experiences of the vicious to guide their judgments” (409b). Unlike geometric models (παραδειγματα), ethical models can have either beneficial or problematic effects for the way a human being conducts his or her life. I will highlight two particular examples in which Socrates demonstrates how beneficial models can be salvaged from problematic shadows for the good.

In Book IV, Socrates makes use of a shadowy image, a ειδωλα, in an effort to visualize a model of the tripartite soul. Before he turns to the ειδωλα, Glaucon has suggested to Socrates that the soul consists of two parts – the rational part and the irrational appetitive part. He does not designate the spirited part as a third part of the soul but as of the same nature as the appetitive part. Socrates, in an attempt to convince Glaucon of the possibility that the spirit is a part of its own, tells a story about a man named Leontius, who, on his way back from the Piraeus, saw corpses lying at the feet of the executioner. Socrates says, “He had an appetite to look at them but at the same time he was disgusted and turned away” (439e). After an internal struggle with himself, he, overpowered by the appetitive part, pushed his eyes wide open and rushed towards the spectacle, saying “Look for yourselves, you evil wretches, take your fill of the beautiful sight!” (440a).

If we take the story as a whole, Socrates’ description and imitation of Leontius is specific to a point. The character of Leontius is revealed to us, listeners, in this one specific circumstance, and, moreover, the focus is on the civil war that takes place inside him. Although he has a desire to look at the corpses, since supposedly he was known for a love of boys as pale as corpses, he was met with a conflicting “spirit within him, boiling and angry, fighting for what he believes to be just” (440b). The story demonstrates how the appetite can make war against the spirit and “…force someone contrary to rational calculation, [so that] he reproaches himself and gets angry with that in him that’s doing the forcing” (440b). Given Leontius’ surrendering to the appetitive part, one would think that he would be a bad example to imitate. However, Socrates salvages the ειδωλα by depicting the example of Leontius as a model for how the appetitive part and spirited part of the soul are different from one another. Once Glaucon has agreed to this conclusion, Socrates can say “Well, then, we’ve now made our difficult way through a sea of argument. We are pretty much agreed that the same number and the same kinds of classes as are in the city are also in the soul of each individual” (441c). The model of Leontius is a visual of the difference between the appetitive and spirited parts in the soul. Now that Socrates has changed the contours of Glaucon’s imagination with this visual, he can say that the three classes in the city now align with three parts of the soul, and thus he can proceed with his argument.

In Socratic fashion, I would like to zoom out of focus with our microscope and consider the whole work of the Republic as a theoretical model. Socrates says himself in Book VI, almost begrudgingly, "And when the majority realize that what we are saying about the philosopher is true, will they be harsh with him or mistrust us when we say the city will never find happiness until its outline is sketched by painters who use the divine model [οι τω θειω παραδειγματι]?” (500e). As before, Socrates takes the ειδωλα of the poets and fashions a new model from them that reflects the superior benefits of trusting a “divine model”. Recall Book I of the Republic when Adeimantus described the poets' shadow-like paintings of Hades and the potentially harmful consequences that would result from believing in the fabricated stories. Adeimantus expressed his concern to Socrates, saying, “When all such sayings about the attitudes of gods and humans to virtue and vice are so often repeated, Socrates, what effect do you suppose they have on the souls of young people?” (365a).

According to the poets, the gods in Hades are said to “…assign misfortune and a bad life to many good people, and the opposite fates to their opposites” (364c). Living a life of justice and moderation is depicted by the poets as onerous, while leading an unjust life is easy and only shameful in opinion and law. Moreover, the poets' stories persuade whole cities that unjust deeds can be absolved through sacrifice and rituals. Thus, the best life is depicted as one who uses sly cunning to attain rewards unjustly and maintains only “a façade of illusory virtue…to deceive those who come near…” (365c).

Socrates works throughout the dialogue to convince his interlocutors that justice is a virtue beneficial in itself. He constructs a model of the city and the soul to demonstrate the destructive changes that take place when unjust actions are authorized and the benefits that are reaped when justice remains at the helm. His theoretical models strive after the "divine model," because he believes that the gods are leading exemplars of living a life of virtue and are responsible only for the good, never for evil. He thus, at the very end of Book X, constructs a myth of the afterworld of his own, except he demonstrates that the myth can function as a model for the just life. With the Myth of Er, he fulfills the one exception that he adds in Book X which would allow poetry to be included in the καλλιπολις: “Nonetheless, if the poetry that aims at pleasure and imitation has any argument to bring forward that proves it ought to have a place in a well-governed city, we at least would be glad to admit it, for we are well-aware of the charm it exercises…for we’d certainly profit if poetry were shown to be not only pleasant but also beneficial” (607d-e; my emphasis added).

The basis for his theoretical model of the afterworld is that “the responsibility lies with the one who makes the choice” among “models (παραδειγματα) of lives” to inhabit, and that “the god has none” (617e). He gives enormous weight to the life people choose to live in this world here and now, because the character of their former life will determine what life their souls choose to inhabit in reincarnated form. If people learn the benefits of living a virtuous life according to the “good” and the vices of doing irreparable evils in an unjust life through pursuing philosophy here on Earth, they will not be deceived by the shadows (ειδωλα) in the afterworld of dazzling beauty and overflowing wealth. Instead, with their acquired knowledge, they will have the strength to hold “…with adamantine determination to the belief that the best way to choose, whether in life or in death” is to consider “…the nature of the soul, to reason out which life if better and which is worse and to choose accordingly, calling a life worse if it leads its soul to become more unjust, better if it leads the soul to become more just, and ignoring everything else” (618e).

They will have learned that the happiness of life is not determined by choosing the most pleasing of the models (παραδειγματα) presented before their eyes, but by considering the invisible models fashioned in the souls of those who follow the models. For philosophy teaches the less visibly apparent fact that “the arrangement of the soul was not included in the model, because the soul is inevitably altered by the different lives it chooses” (618b). Socrates spoke in Books VI-IX about the five types of constitution and the corresponding five ruling structures in the souls – he determined through dialectic with his interlocutors that the model of a καλλιπολις led by a soul ruled by reason is the happiest, specifically 729 times more happythan the soul of a tyrant (587d). With each step of his παιδεια, Socrates used images, comparisons, paintings, types, and models to make the invisible visible. We learn at the end of the dialogue, through the Myth of Er, why it was so important to cast light upon the unseen virtues: the purpose was “…to enable him [a human being] to distinguish the good life from the bad and always to make the best choice in every possible situation” (618c). He considers it a recipe for cruelty to leave people at their own mercy or the hands of fate, and demonstrates the power of language to indoctrinate a set of beliefs in human beings that does not serve their best judgment. He, therefore, attempts a demonstration of the truth by introducing a new set of skills in language that he hopes will replace the art of imitating with the skill of model-making. If we return to the image of the divided line, we can see that model-making is merely a preparatory third step of Socrates' ladder of παιδεια that prepares students for the harder work of participating in dialectic. According to Socrates, practicing this conceptual visualization is a step towards understanding and articulating the metaphysical truths of the Forms.

Higher Aim of Socratic Paideia: Conversion of the Soul

At the start and the end of the dialogue in the Republic, fictional portrayals of the afterworld are featured in conversation with Socrates as bookends to the core of his argument, which is, namely, that “perhaps, there is a model of it [καλλιπολις] in heaven, for anyone who wants to look at it and to make himself its citizen on the strength of what he sees. It makes no difference whether it is or ever will be somewhere, for he would take part in the practical affairs of that city and no other” (592b). Socrates fanatical cleansing and reordering of the old system of παιδειαin the Athenian polis may seem "impossible" or "theoretical," as his interlocutors note, or even in some respects rather "ugly," as contemporary readers may argue, but his task is not to simply to create a more stable system of laws for a better city-state, as famous lawgivers like Lycurgus and Solon had done, but rather to reconstruct a new polis according to a model of heaven. In some ways, his emphasis on an evaluative or normative politics, with the maxim that the state is a shepherd of the soul, is working towards building a theocracy rather than aristocracy; for even the philosopher-king “paints” a constitution for the polis with the goal of fashioning “a divine form and image” of citizens on Earth.

For Socrates, union with the divine is achieved through intellectual contemplation of the things that exist. We learn from Plato’s Timaeus that God created everything that exists according to an unchangeable pattern, and thus to study the eternal Forms is to study a divine model (28a). Timaeus says of the ‘world-soul’, “Wherefore, using the language of probability, we may say that the world became a living creature truly endowed with soul and intelligence by the providence of God” (30b). Yet, the souls of humans, when encased in a mortal body, are at first without intelligence, so that only through “…true education (παιδεια), he attains the fullness and health of the perfect man, and escapes the worst disease of all; but, if he neglects education, he walks lame to the end of his life, and returns imperfect and good for nothing to the world below” (44b-c).

“True paideia” is not the attainment of knowledge but the molding of character towards the good and the healthy. Yet, Socrates, in the Apology, distinguishes himself from being a teacher, saying, “I have never been anyone’s teacher (διδασκαλος); but if anyone, whether younger or older, desired to hear me speaking and doing my own things, I never begrudged it to him. And I do not converse only when I receive money, and not when I do not receive it: rather I offer myself to both rich and poor alike for questioning, and if anyone wishes to hear what I say, he may answer me. And whether any of them becomes an upright man or not, I would not justly be held responsible, since I have never promised or taught any instruction (εδιδαξα) to any of them” (33a-b). He has no formal students, possesses no infallible knowledge, and does not require fees. His obvious intention is to distinguish himself from professional teachers, the Sophists, who charged for their instruction. The Sophists teach (διδασκω) for the sake of practical wisdom (φρονησις), but Socrates speaks (λεγω) for the sake of a love of knowledge and pursuit thereof (φιλοσοφια). If I may use a metaphor, there is a difference between knowing how to build a bomb and knowing the harm of building a bomb, and the latter sort of knowledge is of the sort Socrates would like to cultivate. He also distinguished himself in the Apology from rhetoricians (ρητωρ), who he defines as clever speakers with no concern for the truth (17b), and from Aristophanes’ mockery in the Clouds that, like a natural philosopher (φυσιολογος), “Socrates is a criminal and a busybody, investigating the things beneath the earth and in the heaven…” (19b).

If Socrates is neither a teacher nor an orator nor a scientist, then what kind of ‘educator’ was he? He does not say explicitly in his own words, but from my study of his particular distinction in language between beneficial and harmful tools of education (παιδεια) as well as his epistemology – knowledge of the truth cannot be understood by ‘sense’ or ‘perception’, but through a transformative cognitive method of learning (παιδευω) -- I conclude that his aim was not ‘to educate’ but ‘to convert’ souls in the proper direction through reforming the old system of education. Education (παιδεια), rather than revolution, was the means by which he hoped to achieve his lofty end of modeling human character after a “divine form and image” so that we serve our innate, rational self-interest by acting in accordance with moral virtues. Socrates speaks of the condition that, I surmise, motivated his search for the significance of ‘virtues’ in Book VI, “Every soul pursues the good and does whatever it does for its sake. It divines that the good is something but it is perplexed and cannot adequately grasp what it is or acquire the sort of stable beliefs it has about other things, and so it misses the benefit, if any, that even those other things may give…” (505e). Like a doctor, Socrates identified the pathology of “good” human character as rooted in the old system of paideia, and he proposed a treatment that aimed to serve the interest of individuals and strive towards a divine model of eternal “good”.

Aristotle the Student: Test Case for Socratic Education

The process of Socratic παιδεια, as I have examined in Plato’s Republic, utilized the power of visuals and symbol-making to prompt a series of cognitive shifts that worked to turn the gaze of souls away from the visible particulars to contemplate the intelligible Forms. One way we can test the effectiveness of Socrates’ method of education is to evaluate its influence on Plato’s student, Aristotle. Aristotle addresses Plato and his writing, therefore I will proceed by addressing the contention between Aristotle and Plato. I hypothesize that, although Aristotle demonstrated interest in the same topics of study as Plato inquired into in the Republic and Timaeus, he relied on composition rather than conversion as a method of transforming his students.

Comparing methods of education

Form and Matter

The end or τελος of Socrates’ παιδεια was understanding the Forms, so that we are “…able to endure every evil and every good, and we’ll always hold to the upward path, practicing justice with reason in every way. That way we’ll be friends both to ourselves and to the gods while we remain here on earth and afterwards…we’ll do well and be happy” (Rep. 621d). I begin with an investigation into Aristotle’s reaction to Socrates’ teaching of the Forms as recounted by Plato in the Republic.

In Metaphysics A, Aristotle writes, “To say that the Forms are patterns, and that other things participate in them, is to use empty phrases and poetical metaphors; for what is it that fashions things on the model of the Ideas?” (Met. 991a). Plato would reply to Aristotle’s quip that the Creator or δεμιουργος he speaks of in the Timaeus is that which fashions the particulars on an eternal model of the Forms. In the ‘Genesis’ chapter, Timaeus says, “Now everything that becomes or is created must of necessity be created by some cause, for without a cause nothing can be created. The work of the Creator, whenever he looks to the unchangeable and fashions the form and nature of his work after an unchangeable pattern, must necessarily be made fair and perfect…” (Tim. 27c). Even this being so, Aristotle still criticizes Plato for his inadequate account of the relationship between the Forms and the particulars as one of “participation” or “resemblance”.

Aristotle continues his line of questioning, “Further, it would seem impossible that the substance and the thing of which it is the substance exist in separation; hence how can the Ideas, if they are the substances of things, exists in separation from them?” (Met. 991b). Aristotle disagrees with Plato that the Forms have a separate existence from the many particulars. He agrees that form and the many particulars, which he constitutes as "matter," are distinguishable metaphysically, but they he disagrees with the notion of their separate existence. In the Categories, Aristotle essentially reverses the relationship Plato establishes between form and particular matter. He considers the ‘primary substances’ to be akin to ‘matter’ and the ‘secondary substances’ to be akin to the Forms. He asserts, “’Animal’ is predicated of the species ‘man’, therefore of the individual man, for if there were no individual man of whom it could be predicated, it could not be predicated of the species ‘man’ at all…Thus everything except primary substances is either predicated of primary substances, or is present in them, and if these last did not exist, it would be impossible for anything else to exist” (Cat. 5). The Form does not exist except in conjunction with matter of some sort. Moreover, contrary to Plato, the Forms cannot exist without individual particulars containing properties.

One consequence of Plato’s notion of the separation of the Form from the many particulars is that it provides a solution to the problem of moral relativism. The Form of "Justice," existing as a separate and independent entity, provides an objective moral standard that stands against the argument that the many acts are ruled “just” only according to each judge’s particular perspective. However, if the Form is separate from the particulars, Aristotle asks, aren’t we left with a metaphysical problem of “what is knowable”? Aristotle and Plato both agree that it is the Form that makes a thing knowable, and thus “…we acquire our knowledge of all things only in so far as they contain something universal” (Met. 999a). If this is so, Aristotle questions “…what on earth the Forms contribute to sensible things, whether eternal or subject to generation and decay; for they are not the cause of any motion or change in them. Againthey are no help towards the knowledge of other things (for they are not the substance of things, otherwise the would be in things), nor to their existence, since they are not present in the things which partake of them)” (Met. 991a).

His method of reasoning essentially follows the idea of genesis: we, human beings, like animals, are naturally born with the power of sense-perception; few in the animal kingdom acquire the faculty of ‘memory’, which retains the things that have been perceived; from numerous memories, we produce an ‘experience’; and, through experience, we acquire both ‘scientific knowledge’ (επιστημη) and ‘art’ (τεχνη). As we evolve as human beings, Aristotle claims, we are changing and moving. Plato does not account for these processes of ‘change’ and ‘movement’ in his static definition of the separation between ‘Forms’ and ‘particular matter’. For how can we evolve to understand the Forms in the world of ‘being’ when we begin with the power of sense in a world of ‘becoming’ full of the many particulars? The ‘turning’ or ‘conversion’ of the soul I identified as a Socratic process of education is in itself a ‘change’ and a ‘movement’ that can find an affinity with Aristotle’s assertions. If the Forms really are ‘abstractions’ (from the Latin meaning “to drag away from”), then something of matter may still cling to the Forms. Thus, the Forms are not a separate entity for Aristotle but something gradually acquired by a process of change.

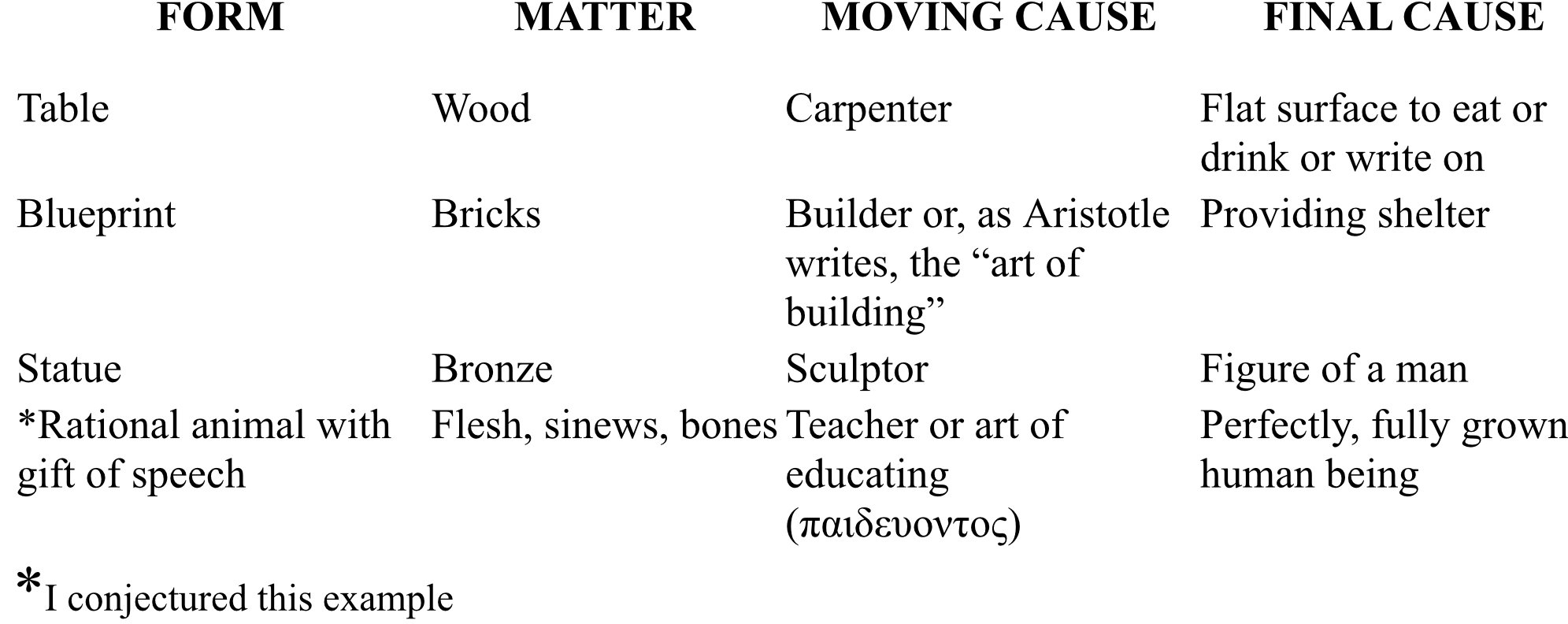

How does Aristotle explain this process of change? He begins by saying that change takes place between opposites (Met. 1018a). On one side lies the Form (ειδος) and on the other side stands the privation (στηρησις). He adds to this binary, which Plato would have been pleased with, a third element: the substratum (υποκειμενον meaning “that which subsists”). The substratum represents the matter which undergoes the change (Met. 1069b). With these three elements, Aristotle considers four potential causes. Here are a few examples of the generative process he has in mind:

As an example of artificial production, the material of wood has a form of the wood in a certain shape which we call a “table”. The carpenter, as the moving cause, performs the ‘making’ of the table for the purpose of the final cause, which is to provide a flat surface to eat or drink or write on. In consideration of our reading of Aristotle, I extrapolate an example of natural production. The form of a human being is essentially a rational animal with the gift of speech, which is made of biological parts, like flesh, sinews, and bones. The moving cause could be his or her ‘teacher’, whose purpose is to fashion a fully developed, grown human being. For Aristotle, objects have their ‘final cause’ in themselves. In order to better elucidate this idea, we must investigate the Aristotelian concepts of potentiality and actuality.

Potentiality and Actuality

In De Anima, Aristotle writes of four pairs that take on the relation of potentiality and actuality: matter and form, the state of knowing and the activity of knowing, body and soul, and perception and knowledge. He writes, “Matter is potentiality and form is actuality; actuality is either, for instance, <the state of> knowing or <the activity of> attending <to what one knows>” (DA. 412a). Then, he relates the soul and body, “The soul is the same sort of actuality that knowing is…Hence the soul is the first actuality of a natural body that is potentially alive” (DA. 412a). Lastly, he says, “Clearly, then, the perceptive part is <what it is> by merely potential, not actual, and so it does not perceive <without an external object>…This is because actual perception is of particulars while knowledge is of universals, which are, in a way, in the soul itself” (DA. 417a-b).

According to each of the four relations, actuality is prior to potentiality, so that formless matter has the ‘potentiality’ of what the end-product is ‘actually’. Aristotle applied these notions of ‘potentiality’ and ‘actuality’ to the process of learning in the classroom. He writes,

“When an understanding and intelligent subject is led from potentiality to actuality, we should not call this teaching but give it some other name. Again, if a subject with potential knowledge learns and acquires knowledge from a teacher with actual knowledge, then we should say either, as we said, that this is not a case of being affected, or that there are two ways of being altered, one of which is a change into a condition of deprivation, and the other of which is a change into possession of a state and into <the fulfillment of the subject’s> nature.” (DA. 417b)

The student has potential knowledge and the teacher has actual knowledge. Teaching, according to Aristotle is a process of alteration or change “…into <the fulfillment of the subject’s> nature”. Aristotle considers education in light of a movement of change, so that a student with potential knowledge can acquire actual knowledge through learning. Note, I describe Aristotle’s views on παιδεια as a ‘process’, ‘movement’, and the participle ‘learning’. ‘Movement’ is not merely an instrument to help move the student from A to B, but movement is the end-product. Movement reconciles the binary of ‘being’ and ‘non-being’, so that when the student becomes ‘intelligent’, he has merely fulfilled the nature of what he actually was already.

However, Aristotle distinguishes between the process of learning that must take place to acquire intellectual versus moral virtues. In the Nichomachean Ethics, he writes, “…intellectual virtue is for the most part both produced and increased by instruction, and therefore requires experience and time; whereas moral and ethical virtue is the product of habit (εθος)…and therefore it is clear that none of the moral virtues formed is engendered in us by nature, for no natural property can be altered by habit” (EN. 1103a). Instruction or παιδεια works with our natures. Since knowledge is a product of intellect and is innate to our human nature, the actuality of knowledge is realizable through παιδεια. Plato considers knowledge of the Good to be the panacea for all crookedness or ugliness of character, and thus he only prescribes a method of παιδεια. However, Aristotle, dissatisfied with Plato’s ontology, adds a distinction between learning intellectual virtue through παιδειαand moral virtue by way of a habitus.

In learning both virtues, he recognizes one common denominator: action (or in Greek, ενεργεια). He writes that students of political science “…have no experience of life and conduct, and it is these that supply the premises and subject matter of this branch of philosophy…the end of this science is not knowledge but action…let us discuss what it is that we pronounce to be the aim of Politics, that is, what is the highest of all goods that action can achieve” (NE. 1095a). We can see why he begins his own study of politics by examining the 158 constitutions already established in Greece. He works through a thorough examination of the particulars towards a knowledge of the universals that comprise of these particulars; then, through a continuous process of change, he works to alter the particulars to build a knowledge and character that aligns with the universal idea of the “Good”.

Since the principle of movement plays such a key role in aiding students to fulfill their true natures, the logical next question is, “Who or what is the ultimate source of movement?” We must look to Aristotle’s views on theology to find an answer.

Theology and Philosophy

Aristotle makes an attempt in chapter 12 of the Metaphysics, also known as Metaphysics Λ, to describe the ultimate source of motion that would align with his account of causation and change. Given the continual movement in the changing objects of the earthly world, the ultimate source of movement must be a mover that is itself unmoved. The ‘unmoved mover’ is a final cause in the realm of immovable things. It dwells in the celestial sphere, where the element of ‘aither’ rather than the four elements of ‘earth, air, fire, and water’ exist. The realm of ‘aither’ allows for a pure substance to exist.

Who or what is this ‘unmoved mover’? Aristotle criticizes Plato for not being able to “explain what it is that he sometimes thinks to be the source of motion, i.e. that which moves itself; for according to him, the soul is posterior to motion and coeval with the sensible universe” (Met. 1072a). He finds contradiction with Plato that the source of movement would be the soul, a movable thing, and relegates Plato’s account to a secondary point. Consequently, he takes a step back to the examine that which has prior existence and intention. He concludes that the final cause must dwell in a realm of immovable things and be both intelligible and appetitable, since the intellect desires an object of thought. He agrees with Plato that the divine is the actuality of thought, but adds that the activity of God must be thought thinking itself. The object of thought moved by the thinking is the result of an animation of desire.

Despite his different account regarding the nature of the divine, Aristotle agrees with Plato that God as “the final cause is (a) some being for whose good an action is done, and (b) something at which the action aims” (Met. 1072b). Aristotle also agrees with Plato that the previous accounts of the divine are false and dangerous, “The rest of their tradition has been added later in a mythological form to influence the vulgar and as a constitutional and utilitarian expedient, they say that these gods are human in shape or are like certain other animals…” (Met. 1074b). Thus, both thinkers agree fundamentally that, in the activity of reason and contemplation, man resembles the divine, and aims towards the final cause of the good.

Reconciling Socratic and Aristotelian Παιδεια

Plato’s Republic serves as a useful guide for decoding the method of learning Socrates proposes for attaining a knowledge of the Good. He utilizes the state as an agent for setting an order that nurtures virtues of the soul. The method he employs focuses on the role of language in learning. He demonstrates how language is a powerful cognitive device for constructing a system of value for a community. Language produces visuals for concepts that human beings cannot see, like the virtues of justice, courage, moderation, and wisdom. Symbol-makers can link the invisible with the visible. He firstly reflects on the language of the poets and the Sophists, who were dominating the free market of speech in fourth-century Greece, as an opening for his critique of images that disrupt the order of human psyche and political society. He follows with a testing of his own theory of language that aims to refashion the political dialogue. He constructs a set of word-pictures that he deems “useful” for their obeisance to the order he has set for the soul and the city. He introduces a new set of vocabulary to differentiate his word-pictures from the shadowy images of the old order. He replaces an art of ‘imitation’ with the art of ‘creation’ through painting, molding, sculpting, comparing, approximating, and modeling.

By equating craftsmanship to moral reform, he demonstrates how reasoning can be visualized and mapped, but in a two-valued approach. We spoke in class about how pragmatists are really Platonists. Platonists introduce binary action as a means of repairing society, because the alternative is habit, conforming to things as they are. Aristotle acquires two lessons of Plato’s method of παιδεια into his repertoire: one, the power of language to alter the course of imaginations; two, the aim of acquiring knowledge of the Good for living a life of happiness. However, he finds metaphysical problems with Plato's explanation of his central concept of the Forms. He reforms the Platonic definition of the Forms to take into accountthe value of the sensible world of particulars. He introduces matter as a ‘third' part, intermediate between Form and privation, that can undergo change and movement through learning to seek perfection of the human faculty of rationality; for virtue is simply the condition of one’s soul which permits consistent and stable, rational selection in agreement with nature. He reconciles the impracticability of the Platonic Forms as something transcendent and separate, and introduces the value of Forms as something that can be brought into actuality during a process of change.

Although Plato was egalitarian in that each person’s happiness mattered equally, he differentiated between the capacities people have to know and understand. Aristotle places more of an emphasis on the student-teacher relationship to work towards achieving one’s maximum capacity for reason through instruction and habit. I can equate Plato’s method to a Rubixcube – he starts with the solved puzzle in the celestial world and works his way down to reconstruct it in the sublunary world. Aristotle, by contrast, begins with an idea of the problems of the world of reality and a rough outline of what he wants to achieve, but maneuvers constantly towards this conception of an ideal. Theorizing for Aristotle is an ongoing relation between θεωρια(observation) and living beings.

The problems that Plato and Aristotle worked to resolve by constructing new ways of learning and interacting in society are not antiquarian. For example, we can see how imitation still plays a powerful role in our culture, in the παιδεια we cultivate as a modern society. A message from the fourth century has followed us into the twenty-first century: that humanity has a duty to change, move, and discover a model for good action that is, most of all, teachable.

Bibliography

Aristotle. Categories. Translated by E.M. Edghill. "The Internet Classics Archive". http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/categories.html

Aristotle. De Anima. Translated by J.A. Smith. "The Internet Classics Archive". http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/soul.html

Aristotle. Nichomachean Ethics. Vol. 19, translated by H. Rackham. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1934. Accessed by “Perseus Tufts”. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0054

Aristotle. Metaphysics. Vols. 17, 18, translated by Hugh Tredennick. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1933, 1989. Accessed by “Perseus Tufts”. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0052%3Abook%3 D12%3Asection%3D1071b.

Augustine, and D. W Robertson. On Christian Doctrine. 1st ed., New York, Macmillan, 1987.

Augustine, Marcus Dods, and Thomas Merton. The City Of God. 1st ed. New York: Modern Library, 1950. Print.

Jaeger, Werner and Gilbert Highet. Paideia. 1st ed., Vo. 2, New York, Oxford University Press, 1943.

Markus, Robert A. St. Augustine on Signs. Phronesis, Vol. 2 No. 1, Brill Publishing, 1957. Pp. 60-83

Ochs, Peter. Post-Liberal Logics & Spirit of Jenson. 2016.

Plato. Apology. Translated by B. Jowett. Ebooks.Adelaide.Edu.Au. https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/p/plato/p71ap/

Plato. Republic. Translated by G.M.A. Grube. 1st ed., Indianapolis, Hackett Pub. Co., 1992.

Plato, Timaeus. Translated by B. Jowett. Ellopos.Net.http://www.ellopos.net/elpenor/physis/plato-timaeus/default.asp

Inwood, Brad and Lloyd P Gerson. The Stoics Reader. 1st ed., Indianapolis, Hackett Pub. Co., Inc., 2008.